The story of a big oil glut is based on some of the worst analysis I’ve seen in years.

I wrote that six months ago, and it’s as true today as it was then. The belief persists, but the evidence that a glut ever existed is weak at best. If nothing else, it’s a reminder of how easily oil analysts and investors mistake a convenient narrative for physical reality.

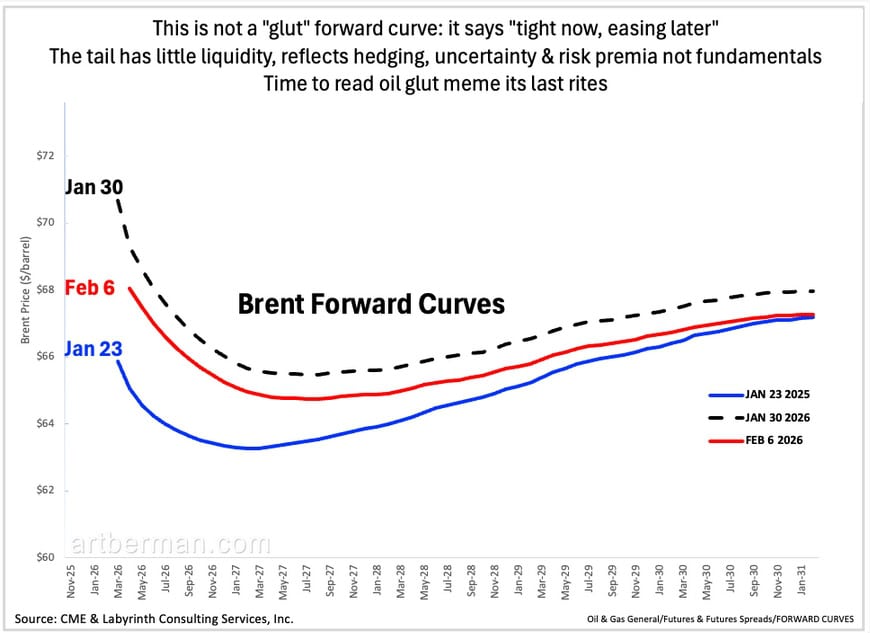

The IEA projected a surplus of more than 4 million barrels per day in early 2026, yet Brent is around $68 and the forward curve remains in strong backwardation through March 2027 (Figure 1). Those are not glut curves. They’re the market saying tight now, easing later. And the far end isn’t a clean fundamental signal anyway: it’s thinly traded and shaped by hedging flows, uncertainty, and risk premia as much as by balances. If the oil glut narrative has any life left, it’s on life support.

Source: CME & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

Looking back over the past six months, it’s hard to make the case that an oil glut ever existed anywhere outside the IEA’s projections and the conga line of groupthink analysts who echoed them. Figure 2 shows representative Brent forward curves beginning in September 2025. They only resemble a glut in October and December 2025. In most other months since September, the curve continued to price tight front-end supply.

100vw, 871px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 2. Brent curves only signaled glut in October and December 2025. Since September 2025, most months still priced tight front-end supply.

Figure 2. Brent curves only signaled glut in October and December 2025. Since September 2025, most months still priced tight front-end supply.Source: CME & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

The problem is that the glut call was built on supply–demand balances. That’s a useful quick-look tool for high-level direction, but those balances are flow estimates. They don’t capture what clears the physical market, and they’re also estimates of an opaque global system, so uncertainty is substantial from the start.

More important, the real world has feedback loops. Inventories, export flows, and OPEC’s response can absorb a surprising amount of imbalance before price has to force producers to cut back. And demand follows economic activity far more reliably than it follows an analyst narrative. A few million barrels per day on paper does not automatically translate into a price collapse.

The Oil Glut Blindspot: The Real World

The biggest blind spot in the analyst story is how geopolitics and real-world events reshape risk perception. The prevailing belief is that geopolitical events are fleeting and have had little impact on markets and prices since the oil shocks of 1973–81. It’s a comforting story. It just isn’t true.

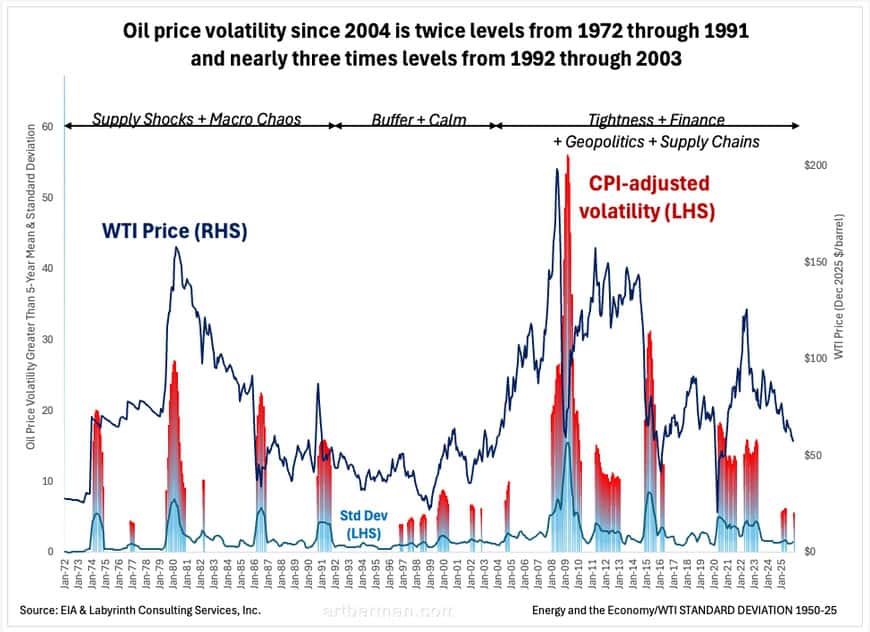

Figure 3 shows oil-price volatility since the early 1970s. I calculated the standard deviation of monthly WTI prices in December 2025-adjusted dollars (light blue line) and then plotted deviations from the 5-year mean (blue and red columns).

The message is clear: volatility since 2004 is roughly double the levels of 1972–1991, and nearly triple the levels of 1992–2003. Not every episode is purely geopolitical, but each represents a shock to the oil market. The larger point is that the system has become more fragile—more tightly coupled, more financialized, and more prone to disruption from multiple directions.

Source: EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

Those changes define three distinct regimes. From 1972 through 1991, oil markets experienced repeated supply shocks layered on top of macroeconomic instability (Figure 4). After decades of relatively flat prices, this was the birth of modern oil-price volatility. It coincided with the end of meaningful U.S. spare capacity, OPEC’s rise as a price-setting force, and successive Middle East disruptions—culminating in the Iran–Iraq War, the 1986 price collapse, and the 1990–91 First Gulf War. High inflation, multiple recessions, sharp interest-rate swings, and the monetary upheaval that followed the end of Bretton Woods all amplified the uncertainty.

100vw, 870px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 4. Oil supply shocks and macro instability characterized the period 1972 – 1991.

Figure 4. Oil supply shocks and macro instability characterized the period 1972 – 1991.Source: EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

From 1992 through 2003, the market entered a relatively calm period, with a few bumps along the way. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, there were fewer global-scale upheavals, and a wave of deepwater oil discoveries helped restore confidence that oil supply could respond. There were still shocks—the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the 1998 oil-price collapse that followed, the 2001 recession, and the 2003 Iraq invasion—but the system was not being hit simultaneously by rapid demand acceleration and repeated supply constraints. In other words, there were relatively few overlapping stresses.

100vw, 870px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 5. 1992 – 2003 was a period of geopolitical calm with economic shocks in 1997-98 and again in 2003.

Figure 5. 1992 – 2003 was a period of geopolitical calm with economic shocks in 1997-98 and again in 2003.Source: EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

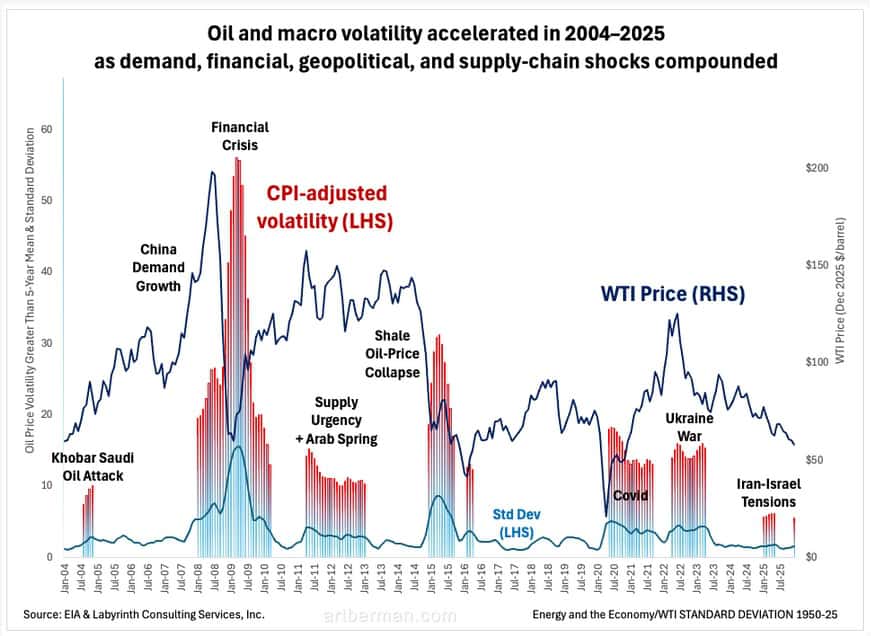

Oil demand and financial shocks defined the early years of 2004–2025; geopolitical and supply-chain shocks compounded them later (Figure 6). China-led demand surged from 2004 to 2008 while global supply struggled to respond, in part because new discoveries took years to reach first oil production. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008–09 was the largest economic shock since the Great Depression. As recovery took hold, supply urgency returned, setting up the longest sustained period of high oil prices in modern history from 2011 to 2014—until shale growth tipped the market and prices collapsed. The Covid-19 pandemic then delivered a combined demand shock and supply-chain shock. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine pushed prices back toward early-period extremes, and the sanctions that followed kept geopolitics central—accelerating fragmentation, trade realignment, and inflation.

Source: EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

The Oil Macro

It’s hard to come away from even a brief review of the past 55 years believing that paper estimates of supply and demand are the dominant forces in oil markets. They matter, but only as one input to a larger set of real-world processes—spare capacity, inventories, logistics, policy, finance, human behavior, and geopolitics—that determine market dynamics. Treating oil as a simple supply–demand spreadsheet is reductionism. It doesn’t just simplify reality; it misrepresents it.

Comparative inventory should be used alongside supply and demand because it helps determine how strongly shocks will move prices. Comparative inventory is a practical measure of supply urgency.

Ordinarily, comparative inventory and oil price tend to move inversely: when comparative inventory is in surplus, prices weaken; when it is in deficit, prices strengthen. But from 2004 to the present, things were rarely ordinary. The system has been hit by near-continuous shocks, and price has often been driven as much by perceived urgency as by the balance itself. Figure 7 shows, for example, that prices rose during the recovery from the 2008–09 financial crisis despite an inventory surplus. The market looked past the surplus because it sensed serious supply urgency: demand was rising and supply was not. That urgency kept prices elevated for years, until the market became convinced that shale growth was durable—at which point prices collapsed.

Lately, comparative inventory has been in deficit, yet prices have fallen because the market has embraced the oil glut narrative and, with it, a reduced sense of supply urgency.

100vw, 870px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 7. When supply urgency combines with tight inventories, prices rise. Without urgency, 2025 prices fell even with tight inventories.

Figure 7. When supply urgency combines with tight inventories, prices rise. Without urgency, 2025 prices fell even with tight inventories.Source: EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

There is a growing sense that the oil-glut story isn’t playing well. Although the estimates of the magnitude of oversupply vary widely, most analysts agree that the surplus peaks in Q4 2025 and Q1 2026 (Figure 8). Yet halfway through Q1 2026, Brent closed at $68 last week. The forecasts implied a price collapse that never arrived. That’s because it was an oversupply, not a glut. The missing ingredient in the glut narrative is the real world: events—mostly geopolitical—supported prices and prevented the kind of capitulation that true glut conditions require.

100vw, 870px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 8. Oversupply isn’t a glut. The surplus is past the midpoint. Combined OPEC–EIA view: surplus peaks in Q4 2025–Q1 2026, then declines.

Figure 8. Oversupply isn’t a glut. The surplus is past the midpoint. Combined OPEC–EIA view: surplus peaks in Q4 2025–Q1 2026, then declines.Source: EIA, OPEC & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

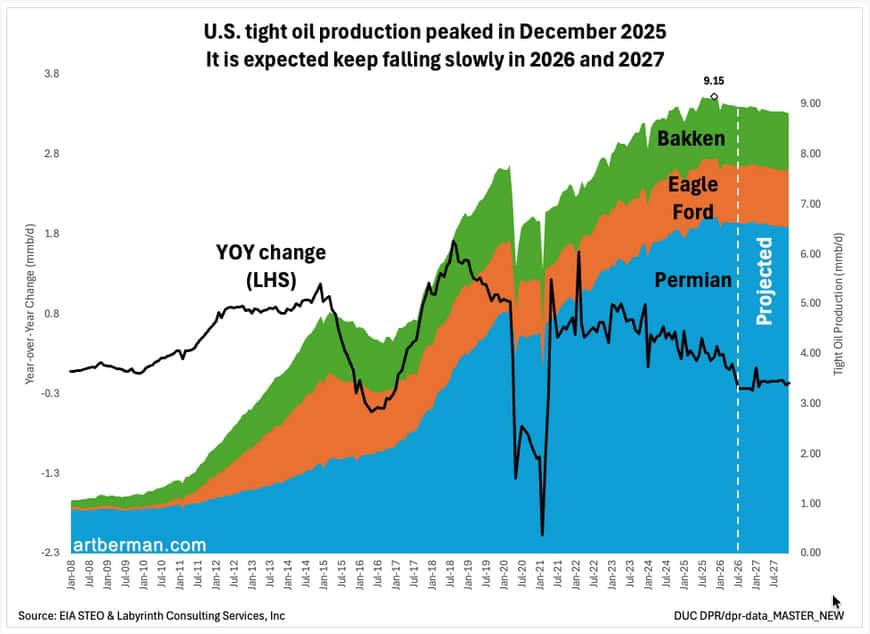

One of the more persuasive arguments against the oil glut story is the visible decline of U.S. shale. The possibility of slowing growth—especially in the Permian—has been debated for years. But the February EIA Short-Term Energy Outlook removes much of the uncertainty: tight oil has peaked, is now in decline, and the EIA expects that decline to continue through its projection window to the end of 2027 (Figure 9). Given that U.S. tight oil has been the dominant source of global supply growth for the better part of the last decade—and the marginal barrel that stabilized markets after 2010—that shift matters.

Source: EIA STEO & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

Peak Oil Reality

It’s unclear whether analysts will ever admit that the oil glut was just the latest in a string of failed narratives—following the “China demand rebound” meme in early 2023 and the “deficit” meme in late 2024. Now that the price outlook is becoming a bit firmer, some are already reaching for the next magical meme: an oil “super cycle” like the one that built into 2008 and persisted, in a different form, until late 2014. I’m skeptical.

The conditions that supported that earlier cycle no longer exist. Global economic growth has ended. The world GDP trendline rose from 1980 to 2006 and has fallen since (Figure 10). That’s important because the correlation between economic activity and oil consumption is structural. GDP and oil consumption rise and fall together.

100vw, 870px» /><figcaption class=) Figure 10. The world GDP trendline rose from 1980 to 2006, and then began to decline.

Figure 10. The world GDP trendline rose from 1980 to 2006, and then began to decline.Source: IMF & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

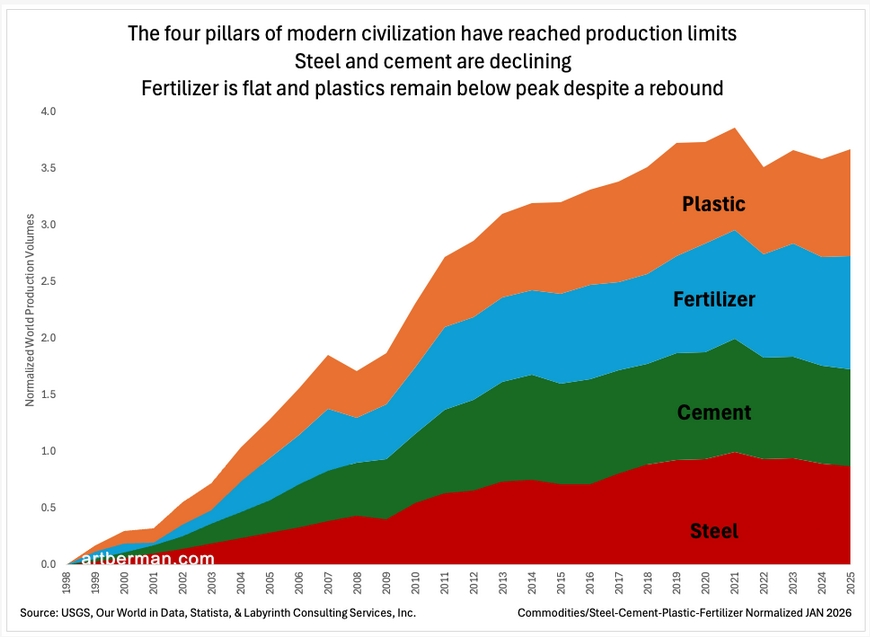

This is consistent with what we’re already seeing in the physical layer beneath GDP. Modern civilization rests on four material pillars: cement, steel, plastics, and ammonia. When these slow or contract, it reflects a declining industrial metabolism. Figure 11 shows that these pillars have already flattened or declined.

Fertilizer is flat and plastics remain below peak despite a rebound.

Source: USGS, Our World in Data, Statista, & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

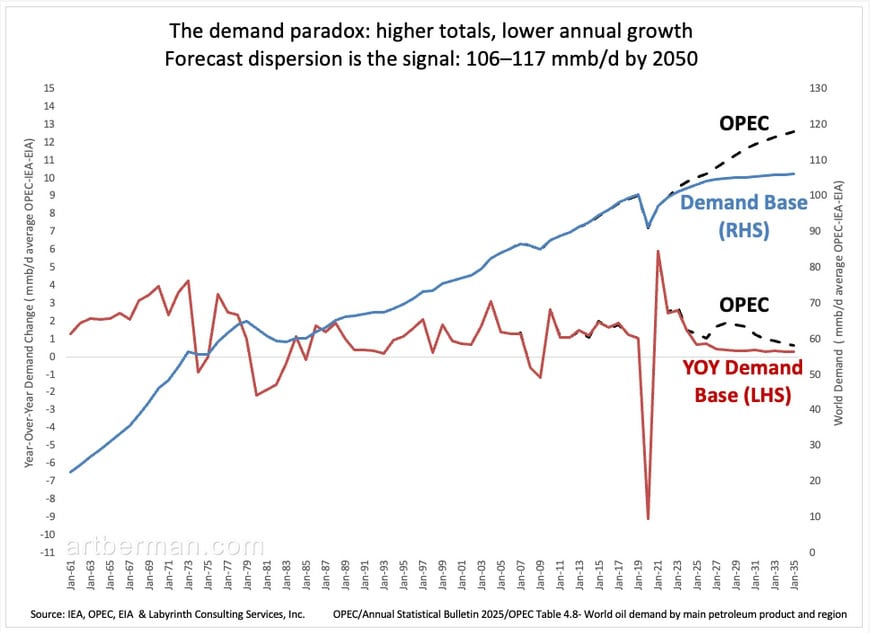

The IEA drew attention last November when it reversed its earlier peak-demand story. In its current policies scenario, oil demand is now projected to keep rising—reaching 105 mmb/d by 2035 and 113 mmb/d by 2050. Many read that as a concession to “climate realism”: fossil fuels remain central, and technology will somehow manage the planetary side effects.

I see it differently. Technology may limit some outcomes at the margin, but its cost benefits will probably be short-lived. More to the point for markets, these outlooks do not change the basic reality that demand growth has probably peaked—and it’s growth, not absolute volume, that drives oil markets and economic expansion.

Figure 12 shows a base-case demand path—a blend of IEA, EIA, and OPEC projections—in blue, alongside OPEC’s more aggressive outlook in black. The spread between them, roughly 106 to 117 mmb/d by 2035, says plenty about how uncertain these long-range forecasts really are. But the more revealing signal is in the year-over-year growth rates (red and black). In both scenarios, demand growth falls to the lowest levels in decades, excluding the one-off collapses of Covid and the 2008 financial crisis. That’s what peak demand looks like: not an abrupt drop in consumption, but a prolonged deceleration toward zero growth.

Source: IEA, OPEC, EIA & Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

Oil prices aren’t rising because optimism has returned. They’re rebounding from an artificially low floor created by a widely believed but false story about an oil glut. The glut never materialized because it wasn’t physical. At most, it was a marginal oversupply—an accounting imbalance amplified by OPEC’s decision to bring withheld barrels back. That was mistaken for the kind of inventory overhang that forces true capitulation. In a spreadsheet world without geopolitics, credit stress, and policy shocks, prices might have fallen further. But that’s not the world we live in.

The past two decades have delivered higher-frequency, higher-amplitude shocks than any period in modern history. That means the margin is always moving. Markets are continually re-pricing tail risk: supply disruption from geopolitics, demand destruction from financial crises, and the growing disorder of a fragmented and adversarial world. In that environment some commodities rally because they are treated as stores of value—hard-asset hedges against monetary and political instability.

Oil doesn’t fit that category. It’s vital to the economy, but it isn’t seen as a store of value. It’s too volatile, too clumsy to own and has no use except to refineries. Compared to other hard-asset commodities, it’s oddly too abundant and difficult to manipulate to trade as anything but risk. That risk can persist for a time, as it did from 2011 to 2014. But even that period was supported by conditions that no longer exist: stronger growth, lower debt, a different monetary regime, and a more coherent world order. Now is not then—and even then, oil was not a reliable super-cycle store-of-value commodity.

We are still far from an outright decline in oil demand, but we are at or near the point where its growth rate enters long-term decay. Producers, companies, and markets are already operating as if they understand this. It’s time analysts and investors did the same.

I’m prepared to read the oil-glut story its last rites, but that doesn’t imply a straight line to $100 oil. In a world of slowing growth, periodic oversupply, and relentless macro and geopolitical shocks, oil is more likely to trade in volatile cycles around a shifting baseline than to settle into a new, durable super-cycle.