Modern hydraulic fracturing – “fracking” – can trace its roots to April 1865, when Civil War Union veteran Lt. Col. Edward A. L. Roberts received the first of his many patents for an “exploding torpedo.”

In May 1890, Pennsylvania’s Otto Cupler Torpedo Company “shot” its last oil well using liquid nitroglycerin – abandoning nitro but continuing to pursue a fundamental oilfield technology. President Rick Tallini says today’s widely used fracturing systems are much advanced from Col. Roberts’ original patents.

“Our business since Colonel Roberts’ day has concerned lowering high explosives charges into oil wells in the Appalachian area to blast fractures into the oil bearing sand,” says Tallini. His company is based in Titusville – where the American petroleum industry began in August 1859 (learn more in First American Oil Well).

Civil War Veteran’s “Torpedo”

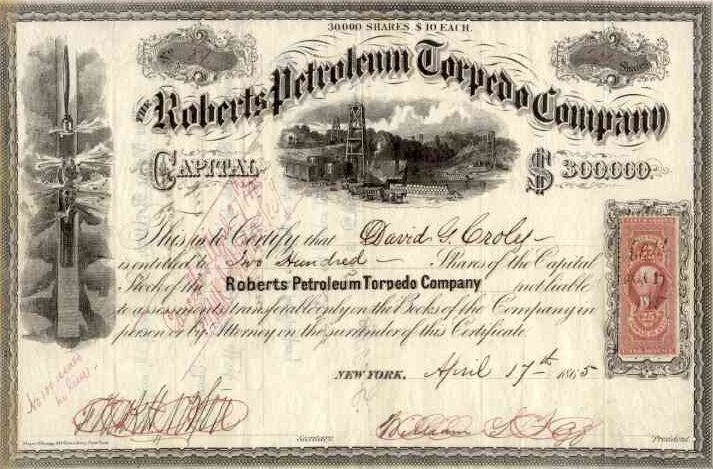

When E.A.L. Roberts founds his company in 1865, his many patents give him a monopoly on torpedoes needed by the oil industry.

Civil War veteran Col. Edward A.L. Roberts fought bravely with a New Jersey Regiment at the bloody 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Amid the chaos of the battle, he saw the results of explosive Confederate artillery rounds plunging into the narrow millrace (canal) that obstructed the battlefield.

Despite heroic actions during the battle, he was cashiered from Union Army in 1863. But the Virginia battlefield observation gave him an idea that would evolve into what he described as “superincumbent fluid tamping.”

Roberts received his first patent for an “Improvement in Exploding Torpedoes in Artesian Wells” on April 25, 1865. His oilfield invention soon greatly increased oil production from America’s young petroleum industry.

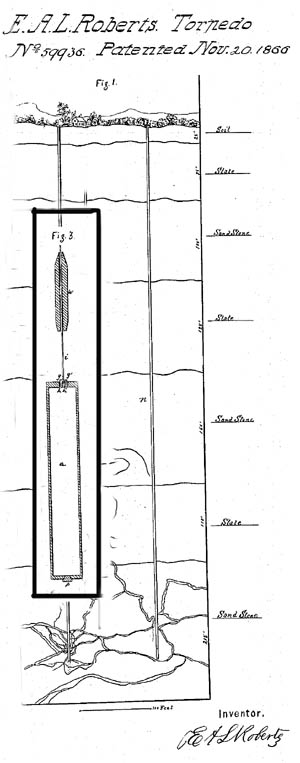

In November 1866, Roberts was awarded U.S. Patent No. 59,936 for what would become known as the Roberts Torpedo. The new technology would revolutionize the young oil and natural gas industry by vastly increasing production from individual wells.

The Titusville Morning Herald newspaper reported:

Our attention has been called to a series of experiments that have been made in the wells of various localities by Col. Roberts, with his newly patented torpedo. The results have in many cases been astonishing.

The torpedo, which is an iron case, containing an amount of powder varying from fifteen to twenty pounds, is lowered into the well, down to the spot, as near as can be ascertained, where it is necessary to explode it.

It is then exploded by means of a cap on the torpedo, connected with the top of the shell by a wire.

Filling the borehole with water provided Roberts his “fluid tamping” to concentrate concussion and more efficiently fracture surrounding oil strata. The technique had an immediate impact – production from some wells increased 1,200 percent within a week of being shot – and the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company flourished.

Roberts charged $100 to $200 per torpedo and a royalty of one-fifteenth of the increased flow of oil.

Attempting to avoid Roberts’ fees, some oilmen hired unlicensed practitioners who operated by “moonlight” with their own devices. The inventor was outraged.

Roberts hired Pinkerton detectives and lawyers to protect his patent – and is said to have been responsible for more civil litigation in defense of a patent than anyone in U. S. history. He spent more than $250,000 to stop the unlawful “torpedoists” or “moonlighters.”

Applied legally or illegally, by 1868 nitroglycerin was preferred to black powder, despite its frequently fatal tendency to detonate accidentally.

“A flame or a spark would not explode Nitro-Glycerin readily, but the chap who struck it a hard rap might as well avoid trouble among his heirs by having had his will written and a cigar-box ordered to hold such fragments as his weeping relatives could pick from the surrounding district,” noted John J. McLauren in 1896 in his book Sketches in Crude Oil — Some Accidents and Incidents of the Petroleum Development in all parts of the Globe.

Otto Cupler Torpedo Co.

Roberts died a wealthy man on March 25, 1881, in Titusville. His heirs sold Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company to its employees, who continued in business as the Independent Explosives Company.

Rick Tallini has related how the Otto Cupler Torpedo Company split off and produced its own nitroglycerin in plants near Titusville until the last plant exploded in 1978. Tallini’s company continued using liquid nitroglycerin until 1990 – when the last of the nitroglycerine supplier’s plant exploded in Moosic, Pennsylvania. A well shooting on May 5 used up the last of Otto Cupler Company’s liquid nitro reserves. Tallini and Otto Cupler Torpedo Company continued shooting wells, but with modern explosives and rigorous safety procedures.

The historic company maintains a museum on Dottyville Road in East Titusville – preserving for future generations remarkable artifacts and documents from more than 100 years of nitroglycerin in the oilfields.

In 1939, Ira McCullough of Los Angeles received patented a multiple bullet-shot casing perforator,”in which projectiles or perforating elements are shot through the casing and into the formation.” McCullough’s innovation of firing at several levels through a borehole’s protective casing greatly enhanced the flow of oil. Learn more in Downhole Bazooka.

First Commercial Hydraulic Fracturing

The first commercial hydraulic fracturing of an oil well took place in 1949 about 12 miles east of Duncan, Oklahoma.

On March 17, 1949, a team of petroleum production experts converges on an oil well about 12 miles east of Duncan, Oklahoma – to perform the first commercial application of hydraulic fracturing.

Later that same day, Halliburton and Stanolind company personnel successfully fractured another oil well near Holliday, Texas.

An experimental well fractured two years earlier in Hugoton, Kansas – home of a massive natural gas field – had proven the possibility of hydraulic fracturing for increased gas well productivity.

By 1988, the technology will have been applied nearly one million times. The technique had been developed and patented by Stanolind (later known as Pan American Oil Company) and an exclusive license issued to Halliburton to perform the process. In 1953, the license was extended to all qualified service companies.

According to a spokesman from Pinnacle, a Halliburton service company:

Since that fateful day in 1949, hydraulic fracturing has done more to increase recoverable reserves than any other technique, and Halliburton has led the industry in developing and applying fracturing technology.

The company representative also noted, “In the more than 60 years following those first treatments, more than two million fracturing treatments have been pumped with no documented case of any treatment polluting an aquifer – not one.”

Issues concerning water withdrawals for hydraulic fracturing in areas of low availability, spills during the handling of fracturing fluids, and injection of the fluids with inadequate mechanical integrity were among issues raised by the Environmental Protection Agency in its 2016 report, Hydraulic Fracturing For Oil And Gas.

Shale Fracturing Technology

In the 1980s, a sudden technological advance in fracturing shale formations led to the U.S. vastly increasing its oil and especially natural production that continues to this day.

Although credit should be shared with others, America’s first “shale boom” began with the innovative thinking of one independent producer from Galveston, Texas, George P. Mitchell, (1919 – 2013). The technology began with steering a well horizontally into producing geological formations.

In the 1980s, Mitchell Energy & Development Corp. began experimenting with hydraulic fracturing in horizontal wells in the Barnett Shale near Fort Worth. The company was one of a few that began finding ways to extract large amounts of natural gas from shale formations. Others followed as geologists recognized the potential of natural gas rich shales in Arkansas and Pennsylvania – and oil shale North Dakota.

In the historic Williston Basin of North Dakota, producing oil since 1951, billions of barrels of new production came from the Bakken shale. Read more in First North Dakota Oil Well.

“There is no shortage of questions about domestic energy production – what technologies are used? What does it mean for our environment? How does it create jobs? What is hydraulic fracturing, anyway?”

The petroleum industry has established websites to educate a skeptical public about fracturing technologies. One – Energy in Depth – offers links to the industry’s research and has noted: “While the first commercial fracturing job was conducted in the 1940s, the technique has been applied to the vast majority of U.S. oil and natural gas wells to enhance well performance, minimize drilling, and recover otherwise inaccessible resources. About 90 percent of the wells in operation have been fractured – and the process continues to be applied to boost production in unconventional formations – such as tight gas sands and shale deposits.”

For another perspective about down-hole explosives to increase production, see Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking.”

Battle of Fredericksburg

For Civil War Buffs: Col. Roberts leads a charge up Marye’s Heights.

The oilfield’s torpedo inventor Col. Edward A. L. Roberts is buried in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

A simple headstone at Woodlawn Cemetery is marked only by his name and the military rank he held at the Battle of Fredericksburg 19 years earlier.

For four months during the Civil War, the man who would someday revolutionize oil and natural gas production technology served as Lt. Colonel with the 28th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Below are rare details from his service records at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Lt. Col. Roberts fought in the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 – while awaiting results from his court martial, which had convened just weeks earlier. As the military court deliberated specifications of “intoxication on dress parade,” Roberts’ regiment marched into Fredericksburg, Virginia.

On December 13, the 28th New Jersey was the center of Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s first doomed assault on the fiercely defended Marye’s Heights. Fourteen more doomed assaults would follow.

The 28th charged into carefully positioned cannons. Confederate Col. Edward Porter Alexander had declared: “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

Alexander was right. No Union soldiers would reach Marye’s Heights that cold December day. Crossing a canal and open ground, brigade after brigade could not dislodge the Confederates from their defenses behind a sunken road and stone wall. Union casualties exceeded 12,000.

When his commander was shot in the face during the 28th’s charge, Roberts assumed command. In his after action report, Roberts wrote, “We went into action under a most galling and deadly fire of shot and shell, and continued in action until near dark. Officers and men conducted themselves well.”

A month later, Roberts’ court martial verdict was published under General Order No. 2. Despite his heroic actions during the battle, among the Civil War’s bloodiest, he was found guilty and ordered to be cashiered, effective January 12, 1863.

Prior to the court’s verdict, Roberts had attempted to resign but this was strangely characterized as “tendering resignation in face of enemy.” Roberts’ service as a Union officer was over in 1863. However, he would soon make history in Pennsylvania oilfields.

Moonlighters shoot Wells

Andrew Dalrymple secretly shot his last well on February 5, 1873, when he and his wife were killed in a nitroglycerin explosion at Dennis Run, Pennsylvania. He allegedly had been “moonlighting” – illegal oil well shooting – in the Tidioute oilfield.

Nitroglycerine was a powerful but dangerous means of fracturing oil-producing rock formations. The technology had been patented, its use rigorously protected. Pouring nitroglycerin was risky enough in the late 19th century. Doing it illegally at night made it more so.

“The Dalrymple torpedo accident at Tidioute brings to light the fact that nitroglycerine, or other dangerous explosives, are used, stored and manipulated secretly in places little suspected by the general public,” reported the Titusville Morning Herald.

“A large amount of this dangerous material has lately been stolen from the various magazines throughout the country, ” the newspaper added. “This species of theft is winked at by some parties, who are opposed to the Roberts torpedo patent.”